500 or So Words About a Song: Dancing Queen

(An occasional attempt to understand why a song works.)

by Paul John Scott

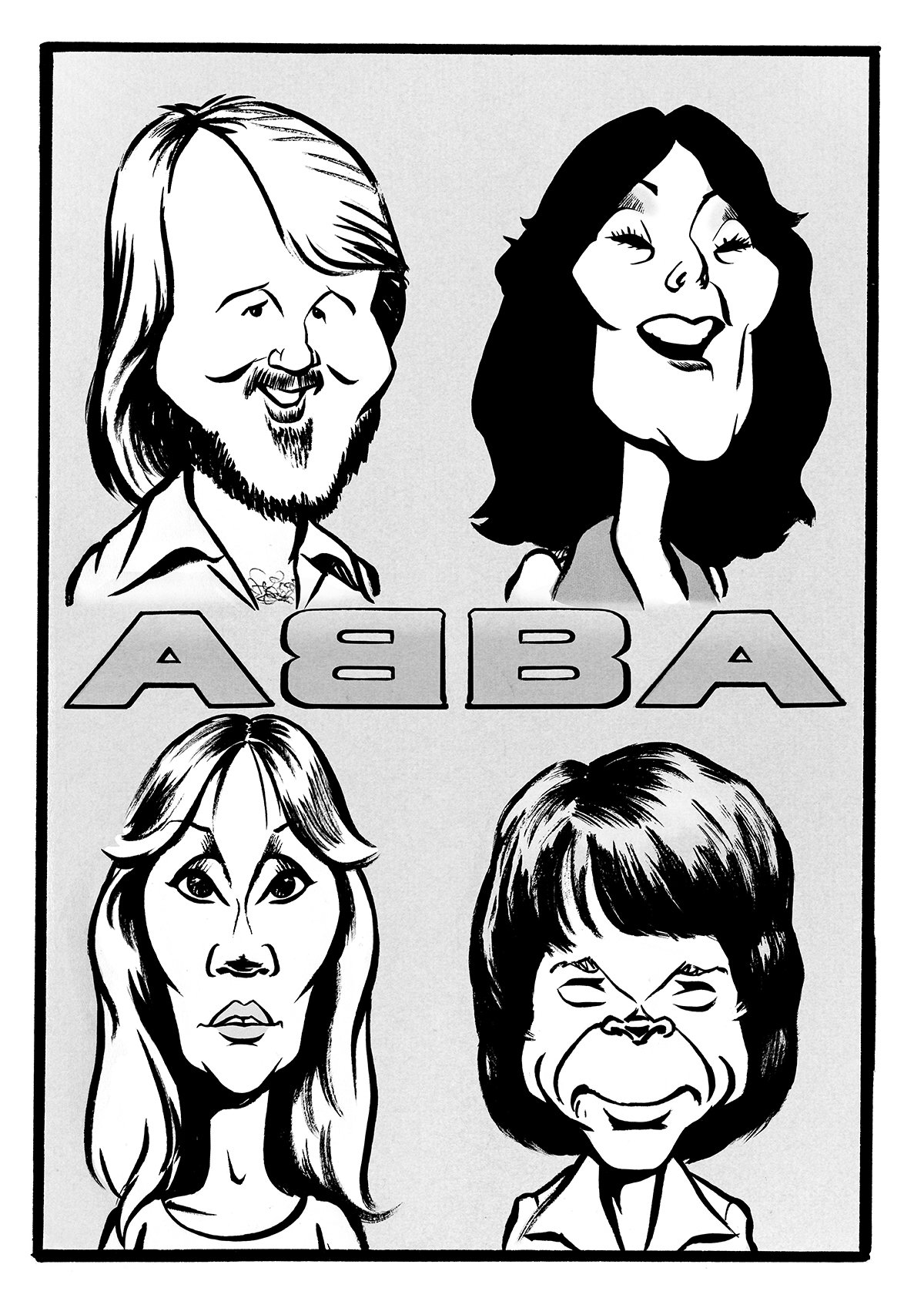

In his new book about songs (World Within a Song, Dutton, 2023), Jeff Tweedy of the band Wilco has an essay about Dancing Queen, the 1976 mega-hit from ABBA.

You may have heard this, the song. It has sold over a million and a half copies, and been streamed something like 93 million times.

Is that a lot? It seems like a lot. It’s hard to tell what a number means anymore.

Jeff writes in this essay how he once hated Dancing Queen, but that he now loves it, having been struck by “how exuberantly sad it was” while staring at a speaker in stunned surprise at a grocery store.

Jeff now believes he only hated Dancing Queen because as a teenager in the 1970’s, “hating certain music gave us a way of defining ourselves,” a practice he now finds embarrassing.

The Times ran an excerpt from this essay, and it’s a great read if you want to look it up.

But I kept hoping for him to explore why Dancing Queen works as a song.

You know, under the hood.

Besides calling its melody "pure and evocative,” the architect of so many arresting songs himself never really got into the nuts and bolts of how Dancing Queen accomplishes its elusive magic of feeling and mood.

Having once learned the ABBA songbook in ridiculous detail for a tribute show several years back, probing that question seemed like a fine way to avoid working on a cold Monday after Thanksgiving. And looking at it up close, the lyrics now seem outdated in places. But the song still seems to still jump out of the speakers, and not just from its wonderful performances or production but down to its bones.

It’s like the Pyramid of Giza.

I had to struggle at getting Dancing Queen out of my brain and onto the piano again. I had to really work at this despite having played the song dozens of times in front of crowds that knew every word.

Having now done that, having found briefly the smile that comes with the rendering of a soaring ABBA confection, I hope to attempt, however foolishly, to explain how I believe Dancing Queen does what it does.

I believe that the genius of Dancing Queen happens something like this.

Dancing Queen opens with the chorus, and not simply at the start of its chorus, but in the middle of its chorus. Which, just...Wow.

It’s like they drop you into the middle of French film, during a DARING CHASE.

As a technical matter, the melody at this mid-point in the chorus -- the heart-swelling part where Agnetha and Anni-Frid sing “YOU can dance,” — has broken like a sunbeam through the clouds as a play between the notes of C# and B, over a chord known as E6.

That's a tension-holding chord – a chord that wants to be somewhere else.

And this is all fine and well.

Many songs do little more than this.

But a Swedish trap is quickly set with a follow-up declaration (“YOU can jive”) using these very same notes, only with the ground underneath that melody having shifted thanks to a new chord known as C# major with a dominant 7.

So the meaning of this C# and B evolves as it becomes part of an entirely different chord.

So for those keeping track, Dancing Queen is just one lyric old and has already arrived at a chord in a different scale, sort of a different musical language, or in visual terms, becoming a Galleon charging over the waves.

I hear in this switch the very sound of courage itself. Set to a lyric about dancing.

And I forgot to say that songwriters, Benny Andersson, Bjorn Ulvaeus and Stig Anderson had somehow descended into this moment with an embarrassing display of showmanship all of its own, placing a succession of urgent chords over their their third or fifths, toying with mood.

After volleying between A major and D major with an A in the bass, this progression had moved effortlessly downward through an E major chord with a G# in the bass, an A major chord, an F# minor and then a delightful A major over an E, all before resolving at E major.

I don’t know why I’m writing this, other than I still remember the thrill when I figured out, after too many hours at the piano, that preposterous A major over its fifth (E), a trick so pristine it isn’t even found in most of the charts you can find for this song online.

They say less is more, but Dancing Queen is one of those instances where more was more.

It’s how a pop song made dancing seem so “exuberantly sad,” as Tweedy says.

Your brain heard an impossibly pleasing escalation of tension through a series of harmonic combinations. And the lyrics said to go out there and dance.

Paul John Scott is a writer and musician who lives in Rochester, MN. He is the author of the novel Malcharist and plays piano in the Shabby Road Orchestra.